Feature Image: José Ferrer

Luxury is often described through its products: rare diamonds, leather goods, perfumes, or couture gowns. But behind every maison that endures lies something less visible: the architecture of its brand. Few people know that structure better than Philippe Mihailovich, founder of HAUTeLUXE, WLCC Honorary Board Member, and one of the earliest thinkers to give brand architecture its academic foundation.

His career path defies linearity: FMCG marketing with giants like Nivea and Wella, the creation of Couture Brands to bring fragrances to designers without them, and finally, advising luxury houses at the highest level. Along the way, he has shaped categories, challenged assumptions, and helped CEOs navigate the delicate balance between immediate sales and long-term identity.

In this conversation with Alexander Chetchikov, President of WLCC, Mr. Mihailovich discusses the recurring challenges luxury leaders face, why sustainability must be treated as an investment, and how ethical sourcing can coexist with exclusivity, and much more.

Alexander Chetchikov: Your career has spanned from working at FMCG brands to creating Couture Brands and then HAUTeLUXE, a strategic brand consultancy business to serve luxury houses (primarily those in high jewelry, leather goods, fashion, beauty, and boutique hotels). How did this broad experience across diverse sectors prepare you to serve as a confidential advisor to CEOs and Chief Branding Officers in the luxury industry?

Philippe Mihailovich: Great Question. A long story.

Actually, as a student, I had worked as a fashion photographer for magazines and newspapers, so I had the chance of seeing that world from the inside and shooting what was to be introduced in the future. I loved the photography of Serge Lutens for Shiseido. He created the first Dior make-up line. Today, he is better known for having started the trend towards perfume as an art and not as a fashion accessory (no male perfume or female perfume). I reached out to him to publish his photos in Creative Photography Magazine, and he ignited my interest in beauty products, prestige branding, and chic cross-cultural imagery.

After my degree I was employed by a top fashion company and received retail management training up to area management level, but hated to be so distanced from the creative side, so I switched to beauty and personal care product management and found that one of the easiest ways to add value to mass products was to look upwards to see what the luxury houses were doing. As such, I found myself eventually working with the same top French Master Perfumers as YSL and Dior were using.

Then when I was responsible for Nivea, I was learning from La Prairie (same corporate group) and when I was at Wella I looked at Professional Salon formulas to improve on consumer products and spotted the opportunity to create ‘designer hair care’ using hairdresser names (e.g. John Frieda, Nicky Clarke) to compete with the faceless corporations such as L’Oreal and Wella. I also noticed that British designers such as Vivienne Westwood, or fashion brands like Monsoon, did not have their own fragrances. I founded Couture Brands to develop those categories. It was such a pleasure working with visionary creatives, founders, and CEOs that I got hooked on it.

AC: At HAUTeLUXE, you sit at the intersection of creativity and strategy, often working with leaders who are under immense pressure to deliver both short-term results and long-term relevance. When these executives bring you their brand dilemmas, what recurring challenges do you see, and how do you help reframe their future into something sustainable?

PM: At first, they were projects primarily linked to brand exploitation, such as brand stretching across categories. The risk of damaging an established reputation is huge. It is what has happened to Gucci, a house that once competed strongly against Hermès in handbags. Not anymore. Under designer Tom Ford, Gucci evolved into a highly successful R2W fashion brand; the style was more American and less Italian, and people seemed to be buying Tom Ford more than they were buying Gucci. The leather craftsmanship heritage of the house collapsed in the process. I’d love the new President and CEO of Gucci, Francesca Bellettini, to call for my help, but she is ex-Bottega Veneta and Saint Laurent, so she is sure to know what to do. The Kering Group also has a new CEO. Let’s hope that I will meet him this year.

To go back to your question, the recurring challenges are remodifying the DNA of a brand and constructing or reconstructing the pillars of its Brand Building before any storytelling begins, which includes brand culture, universe, values, and principles. However, another recurring challenge is when the client feels that they have learned enough from us to go it alone with their commercial team. This happened with an important diamond project, and it all got botched up.

Regarding sustainability, we are already in an “Era of meaningful luxury” and are all seeking the ultimate no-waste circular eco-system. Sustainability must not be seen as a marketing tool. It is an investment. Every manufacturer needs to become sustainable, and luxury houses are in a position to set the example. These houses don’t communicate or position themselves as “sustainable luxury” because sustainability references are mostly rational and tend to kill the dream. Also, many Gen Z say that they want to buy sustainable luxury but will go off to buy something trendy like Jacquemus instead. This suggests that design, social media hype, influencers, and celebrities still carry more weight than sustainable practices.

We believe that all ethical brands have already made significant strides towards sustainable, circular solutions, bio-fabrics, and similar approaches. Hopefully, in the near future, customers will no longer be given the option to purchase anything that damages our planet. Meaningfulness will also imply efforts to eliminate poverty. I’ve been so supportive of Conscious Corporations, such as the Kering Group, and it breaks my heart to see that group suffering a significant decline in sales across its major brands, but mostly Gucci.

We wish them a great recovery. The new CEO must be under immense pressure to deliver both short-term results and long-term relevance; however, the Pinaults (owners of Kering, which owns Gucci) are not known for chasing short-term success to the detriment of their long-term vision.

AC: You’ve been a key figure in academic alliances with business schools in both France and globally. How does the academic perspective at institutions like NEOMA and Toulouse Business School inform your real-world consulting with brands at HAUTeLUXE?

PM: Actually, I was focused more on facilitating alliances between luxury houses and potential retail partners abroad, while also spending five years conducting educational exchanges in China. The academic perspective helps in many ways. Firstly, I’m obliged to keep up with everything going on across the luxury industries globally, as they all change so quickly, and so do the clients. Thankfully, my students are from all over the world, and they keep me in tune with their thinking and desires. I learn so much from their cross-cultural perspectives.

Additionally, I enjoy creating cases for them around brands that I find are weak, lost, damaged, or otherwise struggling, so that I can present students with real-world problems that the brand has not yet resolved. Shang Xia, the Chinese luxury retailer, co-founded with Hermès and now owned by the Agnelli family (Ferrari) is one of them. I always try to develop strategies before briefing the students, and in many cases, I get so excited by these ‘solutions’ that I will try to reach out to the house in the hope that they will commission me to assist them. Some do, and others don’t even bother to reply. Many won’t even recognize the identified problems that they are facing until it is almost too late. The lovely Chinese TTF Haute Joaillerie house, for example.

Shang Xia, after Hermès, made many terrible errors, but it could still be turned into a global powerhouse. I will continue tracking the brand and its actions to further my learning. Whatever solutions the brand may try, I am likely to appreciate them more because I have lived through their problems. Ultimately, my research informs the academic papers I publish, which contribute new findings, key success factors, and the like to the field.

Sadly, I am forbidden from discussing most of our real cases in any form, just as a psychiatrist cannot reveal who his clients are, so I try to find other ways to share the lessons learned. Often, when working with these CEO’s, even their own staff do not know it.

AC: You co-authored the very theories that gave shape to the discipline of Brand Architecture. In your view, how has the science and art of Brand Architecture evolved since those early days, and what function is critical for luxury portfolios navigating the modern era?

PM: Well, considering that my PhD supervisor at Surrey European Management school was not accepting branding or my ‘brand architectural models’ as a legitimate subject. That just shows how far we have come. Luckily, Professor Leslie de Chernatony understood and eventually helped to co-author my first paper, which was published in Volume 1 of the Journal of Brand Management. David Aaker was on the editorial board, and the rest is history. Prof. David Aacker coined the phrase “Brand Architecture,” which I found to be very clever, and with Erich Joachimsthaler, adapted our Brand-Bonding Spectrum to become their Brand Relationship Spectrum. It is thanks to them that the field took off.

At the time, many corporations, such as Accor Hotels, were slapping the corporate name onto every hotel they owned, ranging from the lowest-end hotel, “Formula 1,” to their luxury Sofitel Hotels. It was disastrous for Sofitel, and I was very critical about that. What meaning did they want to give to the brand Accor? Was the promise about great service, meaning I can expect the same level of service in a Formula 1 as I can in a 4- or 5-star Sofitel? In French Accor means agreement. For the hotel guest, it means nothing because it refers to the group being made up of many who agree to fall under that umbrella, and agreements will be entered into with other corporations. A bit like Business Class. The client is the corporation that pays and not the traveler. As such, I thought they were ruining Sofitel. If Accor were symbolic of a promise to offer only organic food in every hotel, it would be more meaningful in attracting guests, even to the Formula 1.

However, it was not a mistake but a deliberate strategy to show massive growth on the stock market to raise the funds to invest in their brands, primarily Sofitel. So as soon as the money was raised, they dropped Accor off the Sofitel signage, shifted all Sofitels up to 5-star hotels, and launched smaller boutique hotels under the So… name, such as So Paris, So New York.

At that time, few companies were thinking it through strategically. The Branding agencies were mostly selling graphic design and would often be the ones to propose brand visuals and sub-brand names. With the advent of the internet, the world quickly became more brand literate and often rushed into creating too many brands and sub-brands for the wrong reasons. The heritage luxury houses stuck to using their house name only, while others created a simple form of brand architecture to support their pyramid structure, for example, Christian Dior Couture at the top, Dior for the R2W, and J’Adore Dior beneath it.

The great Giorgio Armani introduced Armani Privé as a Haute Couture label to try to pull the brand upwards above Armani Jeans, AX, Armani Collezioni, Emporio Armani, and the Giorgio Armani labels, but he never sketched out his pyramid. Retail architects, staff, and licensees (L’Oreal) had to feel it. Hermès has one for their perfume division, but keeps it discreet – although you can find it in our book. Does anyone understand the BOSS pyramid? There’s BOSS and Hugo and Hugo Boss and Boss Green, Boss Orange, Boss Black.

What is critical is not to confuse your customer. For instance, the backlash against some brands that have been selling industrial goods under the very same house name as their handmade luxury goods or special orders. Customers feel that they were duped and are now quite angry and, in some cases, strongly supporting “dups”. Old money defected from brands that were being seen everywhere, and counterfeits helped to over-expose these brands even further. We are now seeing rampant “luxury fatigue” taking place. One of the strategic reasons for artist collaborations was to create a manufactured rarity that not all customers can be seen with the very same bag and offset the risk of over-exposure.

Brand Architecture primarily serves to avoid confusion, to educate, and also enable brand stretching upwards, downwards, or across categories while creating or enhancing a certain pedigree and legitimacy in each category. We are now living in an era that demands transparency, and we believe that Brand Architecture helps to give a certain clarity and thereby a form of transparency. It also serves to highlight expertise and legitimacy.

AC: Scarcity has always been a driver of luxury, yet your current passion for rare, ethical colored diamonds also brings questions of responsibility and transparency to the table. In your opinion, how can luxury houses embrace ethical sourcing without diluting the aura of exclusivity that makes them so desirable in the first place?

PM: Yes, you are absolutely right about that. Transparency can kill the mystique. However, the mystique should ideally lie in the creative den, the little sanctuary of the creator’s mind, and not necessarily in the process of making, and certainly not in the details of the sourcing. Those days are gone. The Blood Diamonds story was shared very widely and obliged mining companies to show transparency, beginning with the person who discovers the stone. Funnily enough, it is now the so-called eco-friendly lab-grown diamonds that are not being transparent, hiding how much energy they are using for CVD (Chemical Vapor Deposition) diamonds and how much coal they are burning to produce HPHT (High Pressure High Temperature) diamonds.

Only solar-grown diamonds can claim to be energy-sustainable, but they all remain soulless, have zero resale value, and do nothing to pull communities out of poverty. The term “scarcity” cannot apply. It is more like buying screws in a hardware store. However, the intense emotion one can feel when holding an unearthed or freshly cut, warm diamond, especially one of color, cannot be explained, and nowadays, rocks are scanned before releasing the diamond from the rock, so the environment suffers far less damage than before. The transparency is there, and that includes the eco-resort plans that kick in once a mine is depleted.

We should also understand why certain houses cannot reveal with full transparency where their craftsmen are to be found, especially in high jewelry, not only for security reasons but also to prevent competitors from poaching these craft masters, who may be independent contractors. Perhaps the rule should be, “As transparent as possible, as secretive as necessary”.

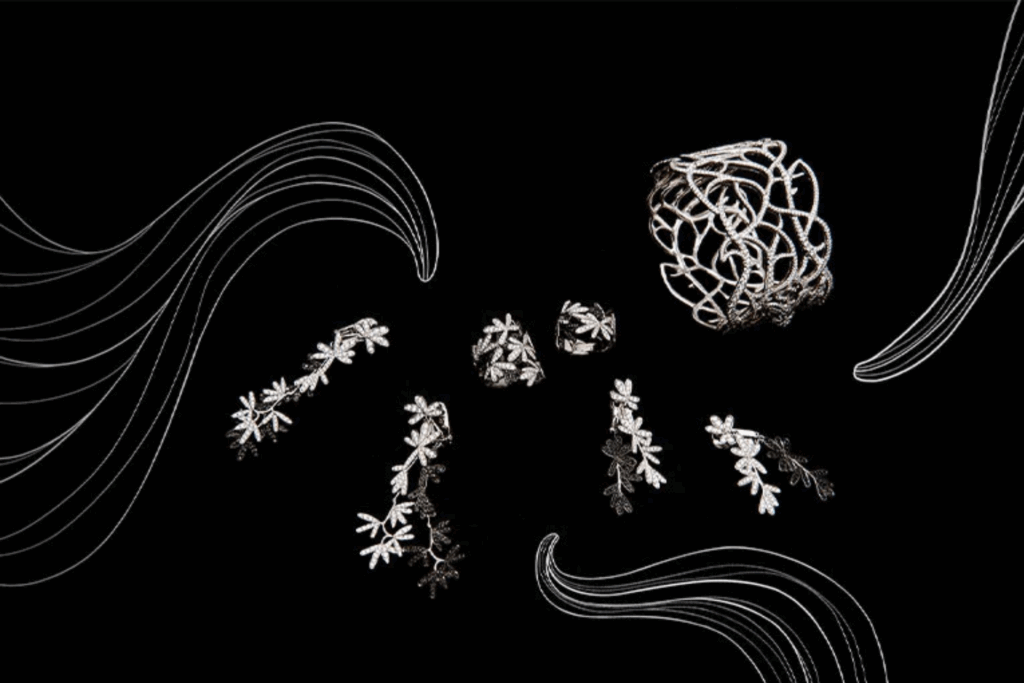

Above: Ombre & Lumière Collection, Lorenz Bäumer

AC: From pioneering masstige haircare to sparking the designer fragrance wave, what’s the most valuable lesson from those earlier breakthroughs that continues to shape how you guide luxury brands today?

PM: Some small lessons were most valuable. For instance, to discover how much the consumer was prepared to trust a brand that carried a person’s first and last name over a made-up name. For instance, Graff, David Morris, or Harry Winston Diamonds over Pandora. When one’s family reputation is on the line, the owners work harder in honor of their name. They are not hiding behind fake names. This is something we are used to seeing in luxury. Most of them are first and last names, except perhaps Rolex, but that is an industrial brand, unlike F.P. Journe, where each watch is made by only one Master Jeweller.

Perhaps the largest lesson was not to invent fake fairytale stories other than for seasonal collections. The luxury maison requires authentic and meaningful stories. Never lie. So, if we are to construct or reconstruct a brand story, we aim to add real legitimacy. This is what Louis Vuitton did before introducing their perfume collection. They had failed 100 years ago. I suppose that a luxury house making waterproof canvas trunks had no legitimacy in the fragrance world other than for fragrances that go inside the box or ambiance fragrances, but not those to wear on your person.

LV acquired a storied 18th-century ex-perfume manufacturing building in Grasse, the capital of French perfumery. They employed an experienced ‘nose’ who was born in Grasse and is a third-generation Master perfumer. Jacques Cavallier-Belletrud’s CV adds tremendous legitimacy to the house of LV. Additional credibility was given to the building by sharing it with Christian Dior’s perfumers. Luxury requires a Master in the house, unlike Ralph Lauren, which will stick its label on products made by someone else.

Perhaps another lesson was to stick to working with founders / CEOs only because you can be direct with them and vice versa. They listen, are curious, offer great insights, ask sharp questions, and are sometimes quite funny. They understand things quickly and can make things happen. Most are very humble, sincere, and generous. They have nothing to prove to anyone, so they are a real pleasure to serve. However, on this point, we have also come to conclude that “nobody can destroy a brand better than its owner or its managers“. Tesla currently offers a perfect example, as does Boeing.

Above: Turandot Lily Necklace, Anna Hu Haute Joaillerie

Thank you, Mr. Mihailovich!

Philippe Mihailovich’s perspective reveals how luxury today is defined not only by heritage and scarcity, but also by authenticity, responsibility, and long-term brand stewardship. From the evolution of brand architecture to the challenges of sustainability and ethical sourcing, his insights remind us that the future of luxury depends on clarity, cultural relevance, and meaningful leadership at the very top.

For more valuable perspectives from Philippe Mihailovich, make sure to follow him on LinkedIn.